“If writing poetry is hard for you, then you aren’t being honest enough,” said Blanca, sitting cross-legged beside me.

We were 11th graders in high school when I laid out three poems that I wrote for an English class on the floor between our dorm rooms. Blanca’s writing voice is beautifully raw. I looked up to her style, and still do. What I had written didn’t resonate with me, so I asked her for help.

She didn’t mark my poems with red ink or tell me to consider this word over that. She didn’t even read the poems. The fact that they did not feel authentic to me was her only critique.

Maybe I was trying so hard to write what I thought I should write that I lost myself. Puppetering what “should be” felt like writing from a bird’s eye view. On my way up, the strings between the page and my heart snapped, scattering the beads of what I really wanted to say into thin air.

Blanca reminded me that this writer’s block is not a reflection of being a bad writer, but rather a neglect of listening to myself.

I began again.

I spoke to myself about how I was feeling, communicating in my voice, without concern for how it might be nonsense to others. After grounding back into my heart, I took the next step by searching for the words in the works of other authors.

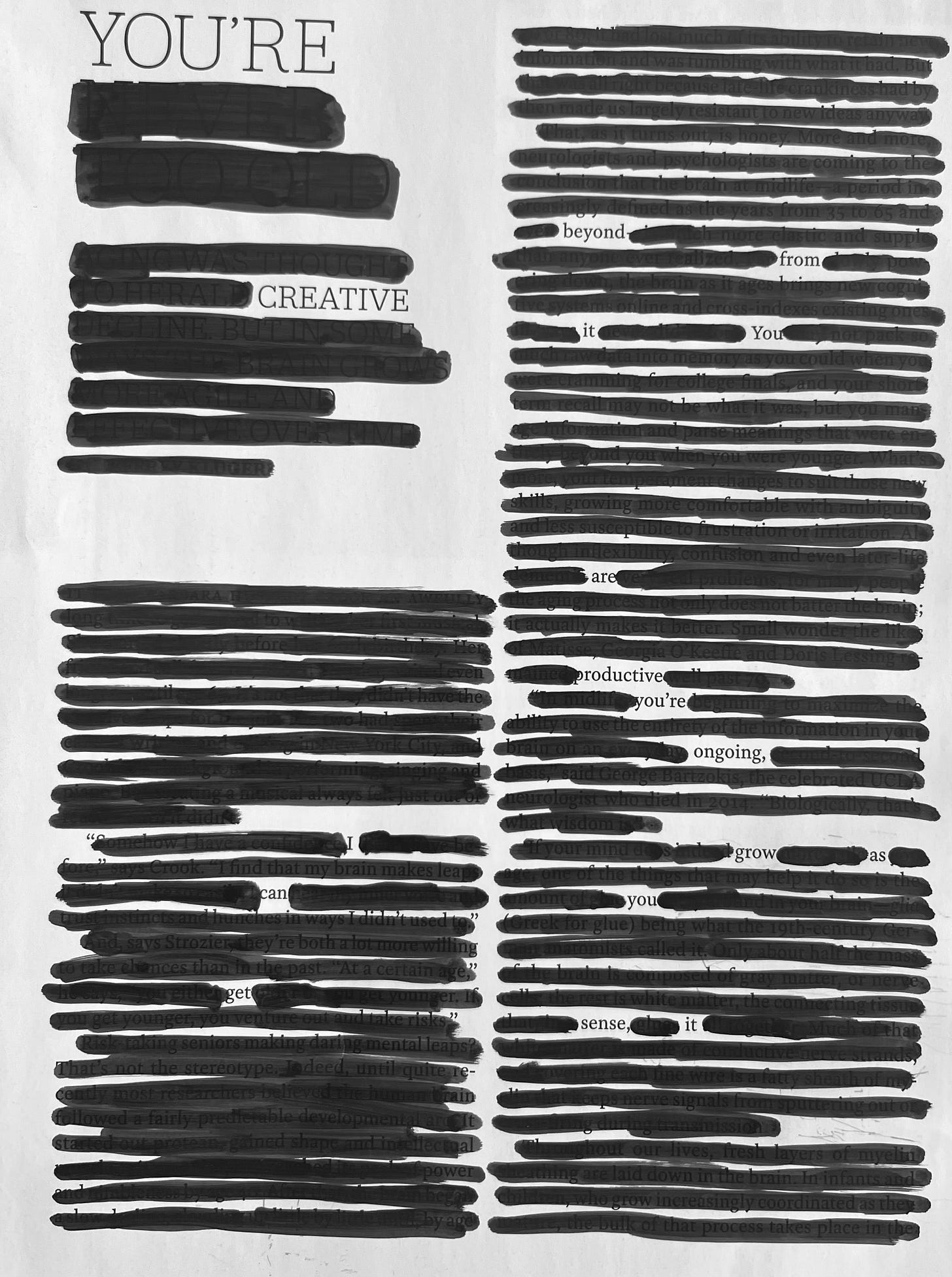

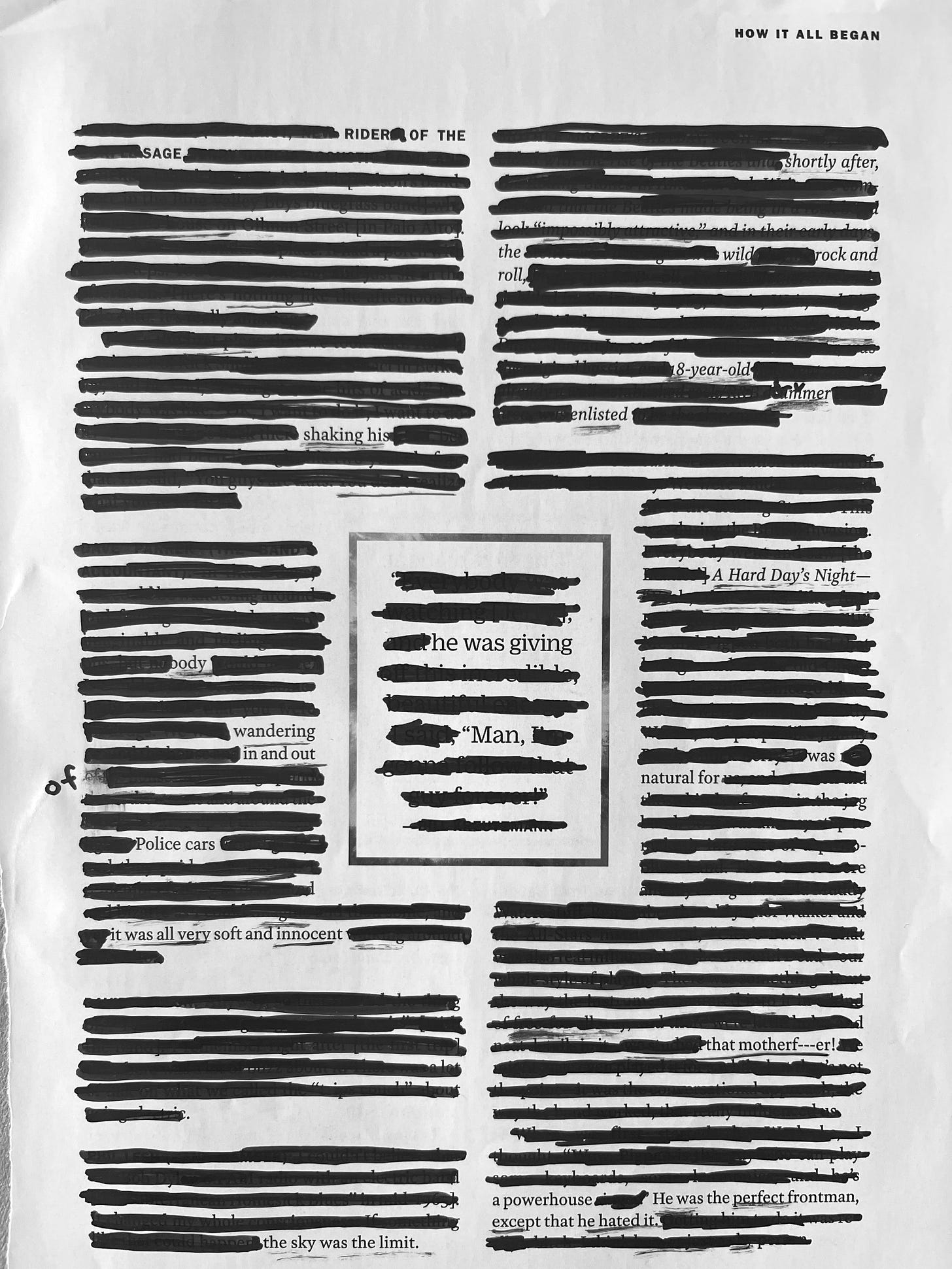

Even today, when I struggle to find my words, I look for them through blackout poetry: taking a page of someone else’s writing and using a Sharpie to black out the words I don’t want, and keeping the words I do want.

Blackout poetry is the inkblot test of reflective writing. Instead of making something out of nothing, I get to rearrange and interpret something already presented to me. Usually, this process reveals my own story between the lines. This makes self-reflection more accessible when I’m feeling lost.

-

With just three weeks before I return to the States, I often get asked, “How are you feeling about leaving?” For the last few weeks, my only honest response has been a somewhat frustrating, “I don’t know.”

“How have you changed this year?”

“I don’t know.”

“What did it feel like when you got here compared to now?”

“I don’t know.”

“What will it feel like to be home and surrounded by old friends and family after all this time on your own?

“I don’t know.”

Not knowing might be more a reflection of overstimulation—so much novelty, and so little time alone to process it—than really not knowing.

After several conversations like this, I decided that it was time to stop sitting in front of a blank page and take scaffolded steps towards deeper reflection, like I did in 11th grade.

I asked my 11th-grade English students to join me.

During this exercise, for the first time this year, the classroom was completely quiet. They focused on their pages and marked them up. Here are two of their pieces they agreed to share publicly:

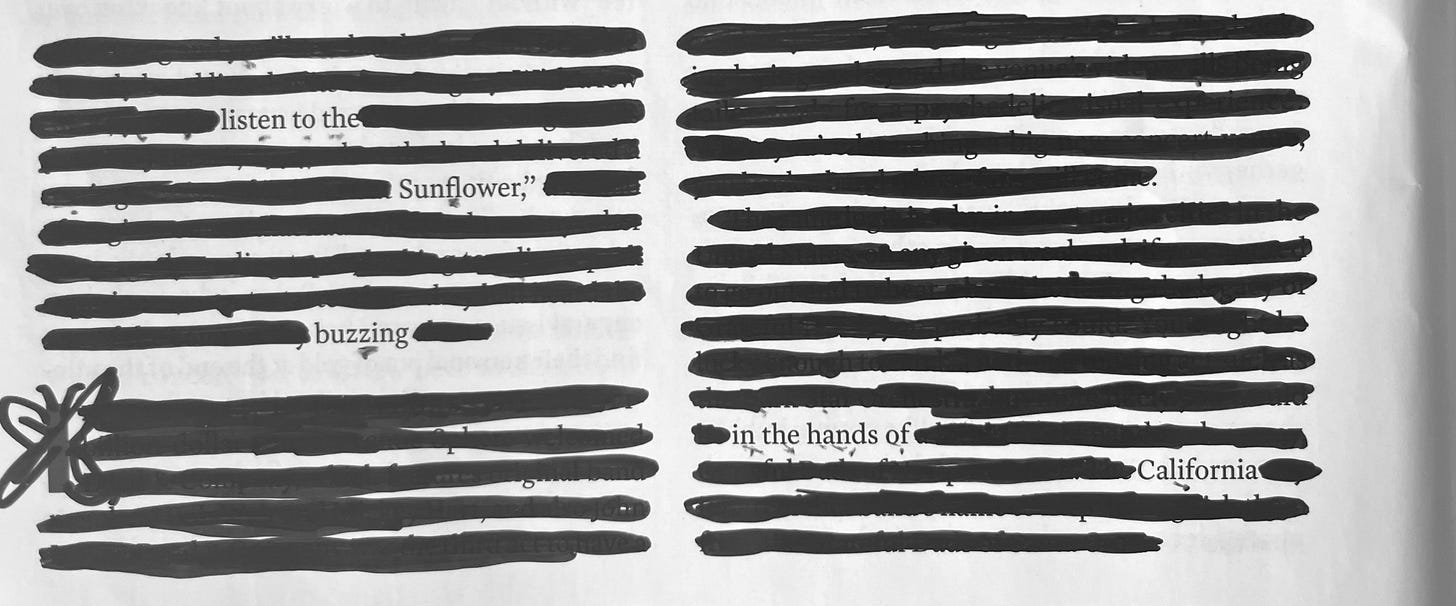

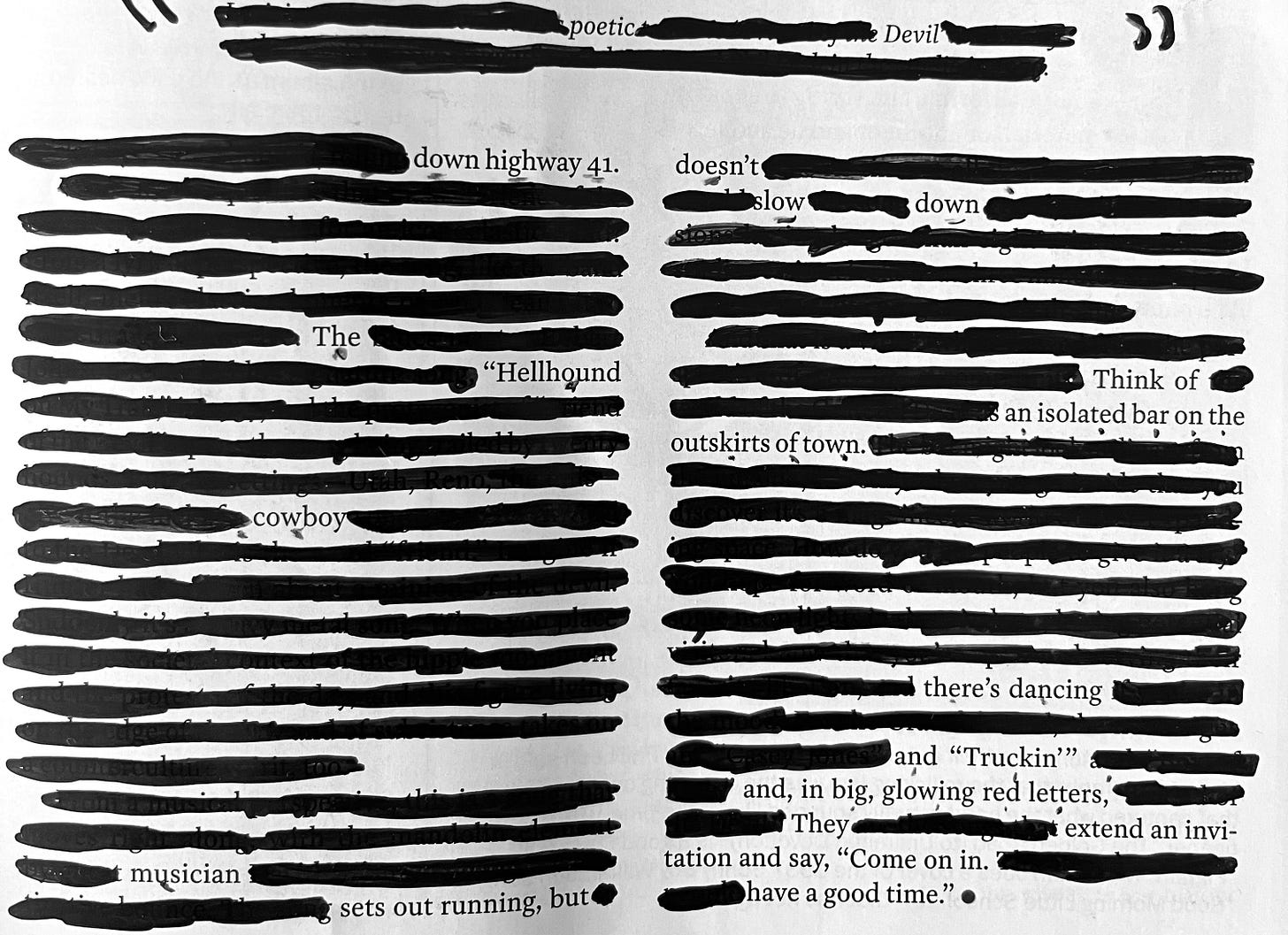

And here are some of mine from pages of Time Magazine’s Grateful Dead “Then. Now. Forever.” special edition from 2024.

After some blackout warm-up, I wrote a poem in my own words for a friend who has recently been my sounding board for dissecting my “I don’t knows.” He asks questions and confronts the incongruity between my sure-sounding voice and creased eyebrows. He demands honesty from myself, for myself.

I would call him on my walks through the sea garden.

Now, it is summer, and a pillowy elderflower musk stirs up my nose, and toddlers play, drifting between radiant joy and sadness.

(I love how toddlers normalize bipolarity. They are acutely alive: organically inconsistent: so unsure about everything that they are moved by anything.)

Dear, I am shy to say this to your blushing cheeks but I looked for your amaryllis in the desert mountains they do not grow in this burning sage dust. still, I tried imagining your widening chest might not find enough breath to keep up— if I beat the odds for you— only sporadic guttural gasps for air as laughter overtook your body a red flower: (i even loved palavering over whether needs water) a promise for zweisamkeit and our blousy, misunderstood hearts thumping blissful beats into the same air. Thank you, You’ve helped me get somewhere.

Through talking with this friend, I’ve started to accept that not knowing might be the Dunning-Kruger Effect of self-discovery. The Dunning-Kruger Effect describes how people with less knowledge tend to overestimate their competence, and those with more knowledge recognize how big the scope of knowledge is, and thus understand just how much they don’t know. In other words, the more you know, the more you know you don’t know.

Thanks to my friends, but most recently the recipient of my poem, this valley of “I don’t know” (how I feel about this year ending) is slowly gaining momentum towards a slope of understanding.

Next time I answer “I don’t know,” I’ll say it more proudly, and maybe follow it with yet.